This section of our website takes an interest in a conundrum within modern-day Australian football: Why all the private Academies outside of clubs?

More emerging everyday across Australia. Private coaching, start up Academies, etc.

Despite record investment in club’s infrastructure, facilities, stadium upgrades, and FIFA grade artificial pitches, these pop-up, very often infrastructure–limited, private organisations continue to flourish. Some now even the size of small association clubs! Why?

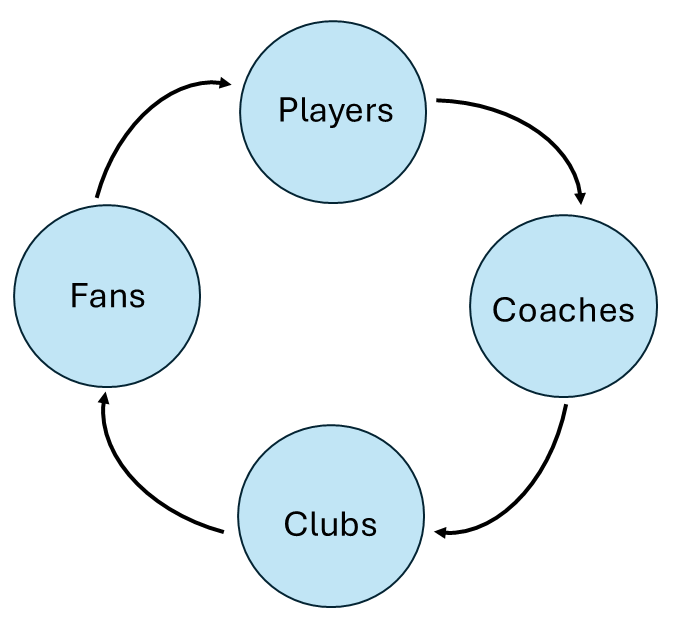

To explore this, we start simple. Consider the symbiotic relationship between the four major pillars of football on both a local and global scale (Fig. 1).

Players play a game. Win or lose. A game is often enjoyed by spectators. Spectators want to enjoy top games. Players want to play in top games. They need to improve. Players rely on coaches, who offer much needed guidance in the pursuit of improvement, whilst, finally, clubs seek to facilitate this three-way transaction.

Clubs offer a ‘home’ for the game, a ‘house’ for the fans, and safe, accessible infrastructure for the coaches. We believe this lifecycle can be visualised at your local association club right through to an elite level football club like Manchester United.

Figure. 1: Our simplification of Football’s organic exchange cycle. People always want to watch a game (fans). Players comprise that game.

Coaches facilitate the development of players, and clubs facilitate coaches, in search developing better players and attracting bigger crowds.

Figure. 1: Our simplification of Football’s organic exchange cycle. People always want to watch a game (fans). Players comprise that game.

Coaches facilitate the development of players, and clubs facilitate coaches, in search developing better players and attracting bigger crowds.

Often one of the pinnacles of public conversation today is the business of professional football. Globally, record investment places this industry at the top of the most desirable to participate in as a professional footballer. ‘Dreams’ are often cultivated as a key marketing message designed to get more of us motivated to participate in the game. Both players and their parents.

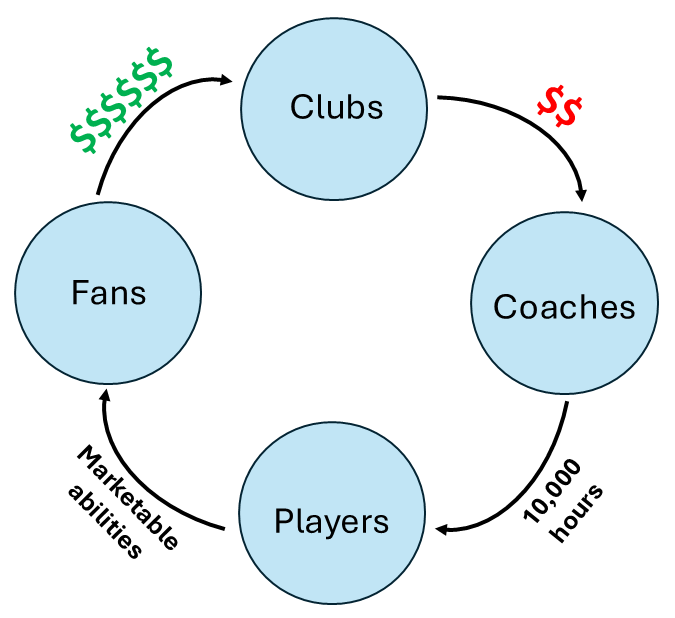

On the path to understanding possible reasons behind the explosion of private Academies across Australia, let’s explore how interdependence within the football lifecycle works in a business setting i.e. the transaction of money (Fig. 2).

We can start with a club (Fig. 2). Motivated by financial flourishment, it has two primary concerns: money in and money out. Simplified, the primary method a club grows its ‘money in’ is through the size of its ‘house.’ i.e. how many fans, sponsors, and viewers can the club attract in a single transaction i.e. a game or season of games. Notoriety/popularity = external investment = money.

To grow one’s ‘house’ there needs to be constant demand for competitive, amazing, technically outstanding players with the single motivation of raising the standard of play, the jeopardy within the game and subsequently the team’s entertainment value through major victories. Winning is the core pillar of prestige within any game or sport. The higher the standard, the scarcer the opportunity, the more accolade the victory holds.

Such a player able to do so takes time to develop. Time. Time. Time. Time to ‘produce’ or ‘build’. From a club’s perspective, this requires an upfront high-risk long-term investment in the child up until very early adulthood in the hope that may one day pay off inside the ‘house’ filled with fans.

Clubs cannot escape this paradigm; they need highly capable players to win them prestigious games. This is obvious. Often lost within realisation is the implicit role of the coach. Coaches are at the centre, the focal point of player development. There is no debating this. From grassroots to foundation football through U’19’s and beyond. Without coaches, players may grow to be raw talented, capable players, but will almost certainly lack the wisdom required to execute such talent under the pressure of expecting paying fans. Coaches are a necessity at youth level. One could argue THE necessity.

Considering this, clubs should invest in well-paid professional coaches. This frees up the most important commodity: their time. With the asset of time now in abundance, coaches can properly invest their focus in the ~10,000-hour development model required to produce a child into a potential professional player with marketable skills, attractive to the spectator. The clubs then bid over these emerging players to play for their teams in the hope they will fill the ‘houses’ with external investment, coming from the fans (as illustrated in Fig. 2). Before any other economics are considered within the business paradigm of football one cannot escape the obvious. It is a talent-driven meritocratic sport. Therefore, the better the player. The better the team, the better the league. The BIGGER the trophy.

Fig. 2: Our simplified model of football’s global modern-day business cycle. Clubs invest in infrastructure,

facilities, and most importantly manpower (coaches) to satisfy the players 10,000-hour time requirement for specialization in football.

These players emerge as young adults with highly desirable skill sets, marketed to the masses in the form of competitive games.

Fans will pay clubs good money to watch these games and admire the competition between skill sets, where the clubs recoup their investments.

Fig. 2: Our simplified model of football’s global modern-day business cycle. Clubs invest in infrastructure,

facilities, and most importantly manpower (coaches) to satisfy the players 10,000-hour time requirement for specialization in football.

These players emerge as young adults with highly desirable skill sets, marketed to the masses in the form of competitive games.

Fans will pay clubs good money to watch these games and admire the competition between skill sets, where the clubs recoup their investments.

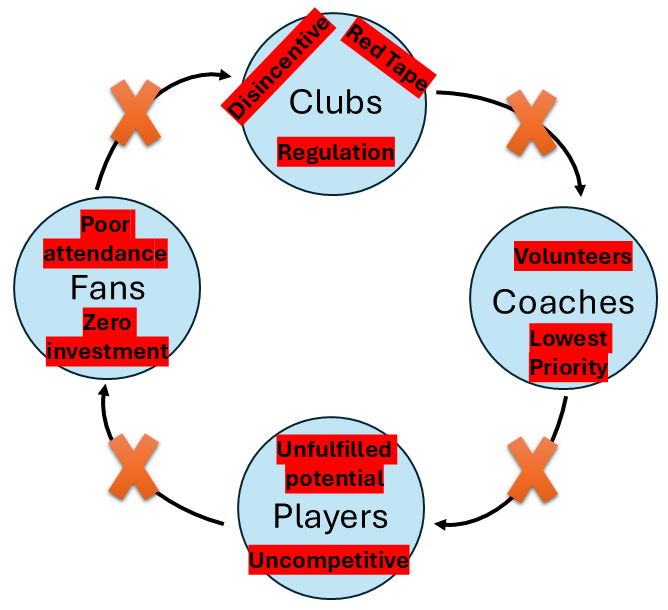

A notable absence of globally marketable Australian players in any top-tier team across the top European leagues (estimated, here, to the ‘pinnacle’ of world football), or even the leagues themselves really suggest we explore the current Australian footballing business lifecycle (Fig. 3).

Currently, several legislative blockades create the disincentive for Australian clubs to act. The list is extensive, however, to choose one and highlight it we can observe the effects of domestic training compensation legislation. Simplified, this legislation imposes price controls on the transfer maximum against a youth player signing their first professional contract. If that fee is capped at a maximum of ‘x-thousand’ dollars, who is going to cover the remaining costs of the 10,000-hour development model? There are many more examples that stifle the future investment into players, contributing to an absence of top top players.

Considering the raft of red tape and disincentives for clubs, they choose not to act seriously about their youth set ups. Relegating the responsibility of coaching young players to volunteers, often parents. This results in an underinvestment in youth development models, and a subsequently malnourished landscape for the players to participate within. This effect is not obvious at first, often only becoming clearer the closer the child approaches adulthood. One’s potential has not been reached.

This ultimately creates a ‘gap’ in the marketplace. Which marketplace? Australian player development. A demand for perceived proper player development and a paucity of its supply amongst established clubs that cannot risk the financial investment required to satisfy this demand. Good ol’ market forces!

Figure. 3: A simplified interpretation of Australia’s modern-day footballing cycle.

Clubs are hampered by red tape and regulation, ultimately disincentivising any investment in the European-equivalent long-term development of youth players.

Subsequently, players emerge as young adults’ uncompetitive on a global landscape. Locally, marketability suffers, and fan investment walks away.

Figure. 3: A simplified interpretation of Australia’s modern-day footballing cycle.

Clubs are hampered by red tape and regulation, ultimately disincentivising any investment in the European-equivalent long-term development of youth players.

Subsequently, players emerge as young adults’ uncompetitive on a global landscape. Locally, marketability suffers, and fan investment walks away.

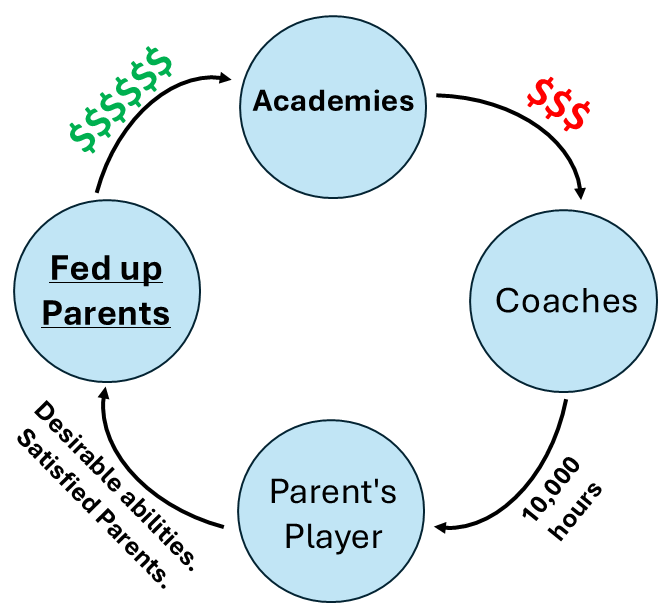

This leads us to explore our conclusion on why Academies are flourishing in Australia. To maintain continuity, let’s look at the role of an Academy in the context of our football lifecycle (Fig. 4). The primary investor now becomes the parent. The parent who will forfeit their time and money to pay a coach to develop their child. To facilitate this established union between paying parent, player, and coach, is now the Academy (Fig. 4). This private institution essentially assumes the role of a club. They provide the upfront financial investment in coaches (paid for by investing parents) that can achieve efforts much closer to the 10,000 hour-development model. Subsequently, the standard of training drastically increases for the player and their development.

This is the proposed motivation explaining the emergence of the private Academy across Australia, and it’s why you’re here on this site. As a parent/guardian/ or aspiring coach, you are searching out for a professional environment that has the key resources required to improve your child or start your career. Turns out, that’s an environment comprised of well paid, experienced, incentivised coaches!

Coaches. That’s it. No fancy stadiums, or gyms, or facilities. Heck! Probably not even a football field itself. A ‘parcel’ of grass will do it. The most important commodity in the development space of football is proper well-paid, professional coaching.

To conclude, this explanation is not an attempt to lay blame at anyone’s feet or critique the current landscape or culture. Rather, it’s to observe and record this interesting Academy Phenomena. Based on current incentive structures within the Australian landscape, our estimate is for the Academy industry to continue its growth, aggressively, motivated by the ever-increasing demand of parents wanting to secure their child’s playing future. Our hypothesis is this leads Academies to ‘replacing’ original foundational clubs in local areas as they evolve into large, cost affordable institutions, themselves.

Figure. 4: Our simplified interpretation on how and why the Academy scene has exploded in recent years across Australia.

Fed up, affluent parents now constitute the bulk of private investment in youth development. Academies replace clubs and attract a wide variety of players

because coaches are now paid a very reasonable wage i.e. ~$25 - $50 AUD per hour. These players emerge with a desirable set of skills that satisfy the parents

expectations of an elite-like footballer and reintegration themselves within the system at a higher level.

There are several examples of professional players that started or spent a significant amount of time at a private Academy in Australia before reintegration.

Figure. 4: Our simplified interpretation on how and why the Academy scene has exploded in recent years across Australia.

Fed up, affluent parents now constitute the bulk of private investment in youth development. Academies replace clubs and attract a wide variety of players

because coaches are now paid a very reasonable wage i.e. ~$25 - $50 AUD per hour. These players emerge with a desirable set of skills that satisfy the parents

expectations of an elite-like footballer and reintegration themselves within the system at a higher level.

There are several examples of professional players that started or spent a significant amount of time at a private Academy in Australia before reintegration.